Via The New York Times

U.S. added 428,000 jobs in April as the labor market remained vibrant.

April produced another solid month of job growth, the Labor Department reported Friday, reflecting the economy’s resilient rebound from the pandemic’s devastation.

U.S. employers added 428,000 jobs, the department said, the same as the revised figure for March. The unemployment rate in April remained 3.6 percent.

“The job market is proving to be a key source of resilience for the economy. Job creation will eventually settle into a slower pace as businesses feel the pinch of soaring inflation and tighter financial conditions, but gains will stay healthy,” said Oren Klachkin, a lead U.S. economist at Oxford Economics. “We think the economy has enough strength to create over 4 million jobs this year.”

The U.S. economy has regained nearly 95 percent of the 22 million jobs lost at the height of coronavirus-related lockdowns in the spring of 2020. And labor force participation has recovered more swiftly than most analysts initially expected, nearing prepandemic levels. The labor supply over the past year has not kept up with a record wave of job openings, however, as businesses expand to meet the demand for a variety of goods and services.

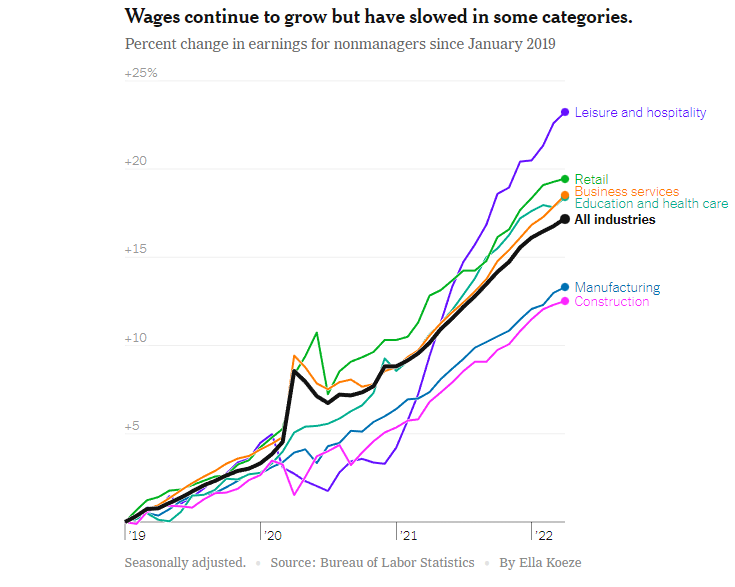

That has helped push up wages — the April survey showed average hourly earnings 5.5 percent higher than a year earlier — but those gains for workers have been largely offset by a surge in prices.

High inflation began last spring as demand from households and businesses collided with a chaotic reordering of the supply of goods and labor, and it has persisted longer than the Federal Reserve expected. The price pressures have been compounded by the war in Ukraine, which has upended energy and commodity markets, and another spell of coronavirus lockdowns in China, which has caused renewed supply chain disruptions.

As a result, the central bank has firmly pivoted to raising interest rates in an effort to cool consumer spending, business lending and demand for workers. If borrowing costs reach what officials call “restrictive levels,” a recession and a reversal of job gains could follow.

A range of analysts believe that increased business costs and labor supply issues may cause the pace of employment to crest soon anyway: The chief economist at Goldman Sachs, Jan Hatzius, recently forecast that payroll monthly growth would ease to 200,000 jobs in the coming months and continue to decelerate.

The U.S. labor force contracted in April, a challenge for employers.

The labor force shrank unexpectedly in April, reversing, at least temporarily, what had been one of the most encouraging trends in the recovery this year.

The slow return of workers to the labor force had been one of the biggest challenges facing the economy last year. As vaccinations spread and consumer demand picked up, employers were eager to hire. But many workers remained on the sidelines, contributing to a labor shortage that made it hard for businesses to find the workers they needed.

Recently, there had been signs that the bottleneck had begun to clear, with several months of strong labor force growth. That made many economists optimistic that rising wages and strong job opportunities, combined with easing public health concerns, would draw people back to work and, over time, resolve the labor shortage.

But that progress stalled in April. The labor force declined by 363,000 workers, and the participation rate — the share of adults who either have a job or are actively looking for one — fell by two-tenths of a point, the biggest one-month drop since September 2020. Labor force participation also fell among adults in their prime working years.

It isn’t clear whether the decline in April represents a one-month pause after a period of strong growth, or a more significant reversal. The labor force data often bounces around from month to month, and economists regularly caution not to read too much into small changes.

Even before the setback in April, however, there had been little sign that the return of workers was making it easier for employers to hire. That’s because demand for workers has risen even faster than supply. Job openings hit a record in March, the Labor Department said this week. There are now 1.9 vacant jobs for every unemployed worker. The data released on Friday suggests the situation won’t be resolved soon.

Even if the labor force returned fully to its prepandemic level, there wouldn’t be enough workers to meet employers’ needs, said Michelle Meyer, chief U.S. economist for Mastercard.

“It’s not about getting supply to where it was prepandemic; it’s about getting supply to meet this very high level of demand,” she said. That, she said, is why policymakers at the Federal Reserve are focused on cooling demand to bring the labor market back into balance.

How and when will the Fed’s rate increases affect hiring?

The Federal Reserve is trying to cool off the red-hot U.S. job market. But it could be months before those efforts start to bear fruit.

The central bank said Wednesday that it would raise interest rates half a percentage point, the biggest increase in more than two decades, and begin paring its bond holdings in a bid to rein in inflation. In a news conference after the announcement, Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, cited the labor market, and in particular the record number of job openings relative to the number of unemployed workers, as a reason that policymakers had become more aggressive in recent months.

“You can see that the labor market is out of balance: You can see that there is a labor shortage,” Mr. Powell said.

Higher interest rates should, in theory, result in less demand from both consumers and businesses, leading companies to post fewer jobs and hire fewer workers. Mr. Powell is hoping that will allow the labor market to rebalance without an increase in the unemployment rate.

But those changes won’t be evident overnight. Interest rates take time to affect the economy, and there are reasons to think the process could take longer than usual this time around. Consumers, in the aggregate, are sitting on trillions of dollars in money saved during the pandemic, and many appear eager to spend it on long-delayed activities like travel. That could blunt the impact of the Fed’s policies, said Michelle Meyer, chief U.S. economist for Mastercard.

“The buffer that’s out there for the consumer is substantial, which means it may take longer to see the impact” of rate increases, she said. “The more resilient the economy is and the stronger it is, the higher the Fed will have to take interest rates in order to see that dampening of demand to depress inflation.”

Still, interest rates will have an effect eventually, Ms. Meyer said. One of the first places that the Fed’s actions are likely to show up is the housing market. Mortgage rates have risen significantly, leading to a steep drop in applications for new mortgages, and there are signs that sales have begun to slow. Construction activity — and construction jobs — won’t respond as quickly, in part because of the longstanding shortage of homes for sale, but eventually building is likely to slow as well.

Manufacturing is also likely to feel the effect of higher rates. But the signals could be hard to interpret: Many economists already expected a slowdown in manufacturing this year as the pandemic recedes and consumers revert to spending more on services rather than goods.

Wage growth moderated in April, a hint of good news for the Fed.

American workers’ wages climbed by a strong 5.5 percent in the year through April, but the pace of increase moderated slightly in the most recent month, which could be welcome news to the Federal Reserve if it lasts.

Average hourly earnings increased by 0.3 percent compared to March, after a 0.5 percent gain the month before.

Fast wage growth is good for workers. But it has also been threatening to keep inflation elevated, both as strong demand persists and as companies raise costs to cover climbing labor expenses.

And while pay gains have been robust, giving households some wherewithal to keep spending even as prices climb, those gains have generally not kept up with consumer price inflation, which ran at an 8.5 percent pace in the year through April.

“Everyone loves to see wages go up and it’s a great thing, but you want them to go up at a sustainable level,” Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, said at his news conference this week. “We’ve got to get back to price stability so that we can have a labor market where people’s wages aren’t being eaten up by inflation and where we can have a long expansion, too.”

Mr. Powell and his colleagues earlier this week raised interest rates by half a percentage point — the Fed’s biggest increase since 2000 — and have signaled that further moves are coming. They are trying to slow demand down and discourage business expansions by making money more expensive to borrow, which could in turn slow down hiring and weigh on wages.

While the April employment report offered some reasons for central bankers to hope that pay growth might be starting to moderate, it’s far from a conclusive one — wage growth is volatile from month to month.

Biden hails job and wage growth as fruits of his economic stewardship.

President Biden praised the latest jobs report on Friday as evidence of his administration’s efforts to rebuild the economy, a message the White House is increasingly amplifying ahead of the congressional elections.

In a statement, Mr. Biden credited last year’s $1.9 trillion stimulus package, as well as the distribution of coronavirus vaccines, for the addition of 428,000 jobs in April and for the low unemployment rate of 3.6 percent. Mr. Biden has sought to highlight job creation and wage growth, even as Republicans have said his stimulus package contributed to a spike in prices on goods that has fueled frustration among voters.

“We are building an economy that values the dignity of work,” Mr. Biden said in the statement. “There’s no question that inflation and high prices are a challenge for families across the country, and fighting inflation is a top priority for me,” he said, adding that the economy “faces the challenges of Covid-19, Putin’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, and global inflation from a position of strength. There’s more work to do.”

During a visit to Ohio on Friday, Mr. Biden said the passing of legislation that would pour $300 billion into scientific research and development and shore up domestic manufacturing would create jobs and address supply-chain shortages that have contributed to inflation.

“These manufacturing jobs matter because they fuel our economic growth,” Mr. Biden said. “They fuel exports, and as we’ve seen, they can fuel innovation.”

Mr. Biden also said the bill would “address what is on everyone’s mind: fighting inflation, getting prices down.”

Ronna McDaniel, the chairwoman of the Republican National Committee, issued a statement about the jobs report that put the spotlight on soaring inflation. “Families can’t afford food and groceries, wages can’t keep up with inflation, and Biden’s agenda is only going to make it worse,” she said. “Voters squarely blame Biden and the Democrats for the harm they are causing struggling families across the country.”

But Mr. Biden’s defenders said the report pointed to an environment in which workers could pursue better career opportunities and higher wages. Representative Robert C. Scott of Virginia, chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee, said the data “reflects another outstanding month of job growth and economic recovery.”